One-hundred and five years ago today, a gold miner from California arrived at the doorstep of Herbert Chaffee, the president of the Amenia and Sharon Land Company, in Amenia, ND. This seventy-something, gray-haired man called himself John Armstrong, and he believed Chaffee to be a long-lost uncle. Having established their family trees didn’t cross branches, Armstrong brought up a deal that Chaffee couldn’t refuse: a loan with gold held as collateral. This wasn’t just a few nuggets for a bit of pocket change: Armstrong’s collateral was over a hundred fifty pounds of gold worth $40,000 at the time. At about 2,000 ounces, this would be over two million dollars of gold at today’s prices, but even at the inflation rate $40,000 is worth over a million 2013 dollars. Chaffee offered $30,000, but Armstrong played it conservative and insisted that $25,000 was all he needed.

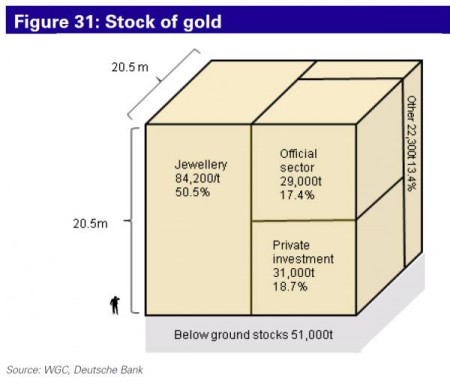

Gold scams have been going on for centuries, as long as people have ascribed a precious desire for the shiny gold metal. All the gold that has been mined, ever, out of the entire history of mankind, would form a cube about 60 to 80 feet on a side, depending on who you ask. That’s even accounting for the fact that gold mines are still in operation, and amateurs and professionals alike head down to the river with a pan and high hopes every day.

There’s other ways people intend to get their gold, though, and not on the open market. The ridges on your coins harken back to days when people shaved off the edges of coins, making them imperceptibly smaller but still appearing to have their full value. People would put coins in a bag and shake them around, causing a bit of gold dust to get rubbed off; other soaked coins in acid briefly to take a layer off, to be decanted from the corrosive fluid later.

Chaffee tried to head off being scammed: his son, Eben Chaffee, was a gold assayer, so Herbert brought Eben along to Minneapolis to evaluate the old miner’s gold. The three men went to where the gold was stored, and a drill was used to get a small sample.

Just testing the outside of a bar of gold is the least reliable way of testing it: gold leaf can be only a few atoms thick and a layer can make a chunk of lead appear to be a solid bar of gold. Reports of desperate-sounding people peddling 5oz gold bars at malls has relied on this trick. Scammers bought real bars of gold and filled the centers with a non-precious metal, keeping what they removed and selling the much-smaller amount of gold to gullible customers at full price. So, you take a core as deep into the gold as you can get, also to make sure that the gold is of a consistent quality throughout and not just quality-gold on the outside.

Armstrong got the names of a few independent, impartial assayers to get the gold tested. Eben Chaffee made arrangements to purchase some nitric acid, a component of the test for gold content, from an outside source to guarantee accuracy. The three men took their little shavings to assayer W. H. Harper and had him perform the test. Harper’s result: the shavings were the highest quality gold, almost completely pure. The Chaffees cashed a check for $25,000 and gave Armstrong his loan in cash.

It’s no wonder that both Armstrong and Harper disappeared shortly after.

Their scam didn’t rely on adulterating the gold or covering base metals with precious ones. Armstrong — not his real name — relied on a confidence game. His story was believable: he, of course, had the name of a reliable assayer; and he was happy to let the Chaffee’s bring whatever testing materials along they liked. Armstrong knew that once they got to Harper’s office the test was going to show the gold bars to be real gold,and then the Chaffees would be hooked.

Herbert Chaffee was out $25,000, over a million dollars in today’s money, and what he had to show for it was 80 pounds of polished brass. The Chaffees missed one of the more obvious gold tests: gold is a very heavy element, and a scale could have quickly identified the scammer’s metal as something other than gold.

And Armstrong, whose real name was so inconsistent in the papers that I’m not even sure which is correct, would have gotten away with Chaffee’s money if he hadn’t gotten caught performing the same scam on a woman in Ohio. Back in his home state of California, Armstrong paid his bail and was left to his own recognizance pending his extradition court appearance.

He missed the trial and a few days later a body washed up on shore. Armstrong’s wife and a “business associate” were both quick to identify the body as Armstrong’s. With little other evidence to go on, the case was closed…but police were suspicious at the circumstances of Armstrong’s supposed death. Both California authorities and the Minneapolis detectives sent to extradite Armstrong believe it wasn’t the old “miner’s” body. It was one last switcheroo, brass switched for gold, to let the con man get away.