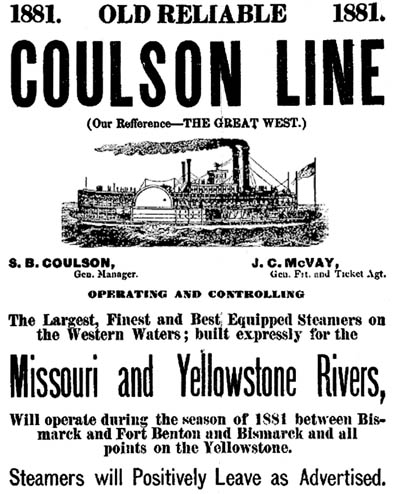

Today’s Dakota Death Trip has a striking soldier in uniform for the Sunday photo; he may seem like the wrong sort of image to post for Memorial Day weekend. Thick mustache, guns stacked to the side, and the kind of helmet the Kaiser would praise a solder for keeping in good shape.

That iconic helmet induces people of the 21st century to remember trench warfare, the earliest of tanks crushing everything in its path on the Western Front, and America’s mortal enemies wearing little close-fitting helmets with spikes on top.

Looking back at an earlier time through the filter of modern day has its pitfalls: it seems like every couple days the internet realizes the swastika wasn’t originally a symbol of fascism and genocide. We see the above photo as the enemy, because one of the most destructive wars ever fought was against an army of helmets like this. However, that was all in the 1910s, due to political strife of the time, the terrorism of anarchists fighting against the empire swallowing their smaller nations, triggering a war that spanned a continent. When this photo was taken, America wasn’t shipping our doughboys ‘over there.’ German immigrants were flowing into the midwest, inspiring the railroad to name a fledgling frontier town after German Chancellor Otto von Bismarck, eventually becoming the state capitol.

![tumblr_mxq5y29p2u1rwjpnyo2_1280[1]](http://www.infomercantile.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/tumblr_mxq5y29p2u1rwjpnyo2_12801-449x613.jpg)

The spiked helmet is known as a pikelhaube, and while it did have its origins in the Germanic regions of central and eastern Europe, there’s nothing sinister about its origins. Today’s military uniforms are plain and functional, and that change was slow and started in the 19th century. Military uniforms were a symbol of power, a demonstration of a country’s military strength, and the pikelhaube was an iconic part of those uniforms.

As is with other aspects of fashion, various designs similar to the pikelhaube spread through other militaries around the world, including South America, Russia, and Scandinavian countries. The British Horse Guard still wears them, in polished metal, and the design is still present, if you know what you’re looking for, in the traditional bobby helmet. And, as a young country not wanting to buck popular fashion trends, the US military adopted it as well.

![6488a59b7c3e1707c90b4d34897826bf[1]](http://www.infomercantile.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/6488a59b7c3e1707c90b4d34897826bf1-450x585.jpg) The pickelhaube first was worn during the Civil War, by German militia regiments; the militias were self-contained units, not affiliated with the standing US Army, so they were able to design their own uniforms. The militias also pulled from their local communities, which were often of similar ancestry, so a more German region would choose to base their uniforms on the ones they would have work back home. In this case, they adopted the pikelhaube.

The pickelhaube first was worn during the Civil War, by German militia regiments; the militias were self-contained units, not affiliated with the standing US Army, so they were able to design their own uniforms. The militias also pulled from their local communities, which were often of similar ancestry, so a more German region would choose to base their uniforms on the ones they would have work back home. In this case, they adopted the pikelhaube.

This wasn’t a one-off uniform for the Civil War, honoring the homeland; as the pikelhaube spread around the world, the US Army also adopted it as part of the standard uniform through the 1870s and 1890s, although most modern document credits the British calvary as the inspiration for the American helmet, rather than anything German. Let’s take a closer look at our man’s helmet insignia:

That is clearly the traditional American eagle: shield on its chest, holding an olive branch of peace in one claw and arrows of war in the other. This looks like the M1881 helmet (as opposed to the M1872, which does look more British), and the braid would seem to indicate an officer.

I couldn’t definitively identify the coat our helmeted gentleman has on, it doesn’t look standard nor does it show any rank to indicate an officer. The standing collar has a number “1” on it, which could indicate either the 1st Cavalry or 1st Infantry — or, this is possibly a militia uniform, designed after the US Army uniform but given their own unit personality.

So, Dakota Death Trip’s photo today isn’t one of the enemy, or of a German fighting for his empire — but an American soldier, the kind of which we honor on Memorial Day.

![American_Pickelhaube_1489326726[1]](http://www.infomercantile.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/American_Pickelhaube_14893267261-450x479.jpg)