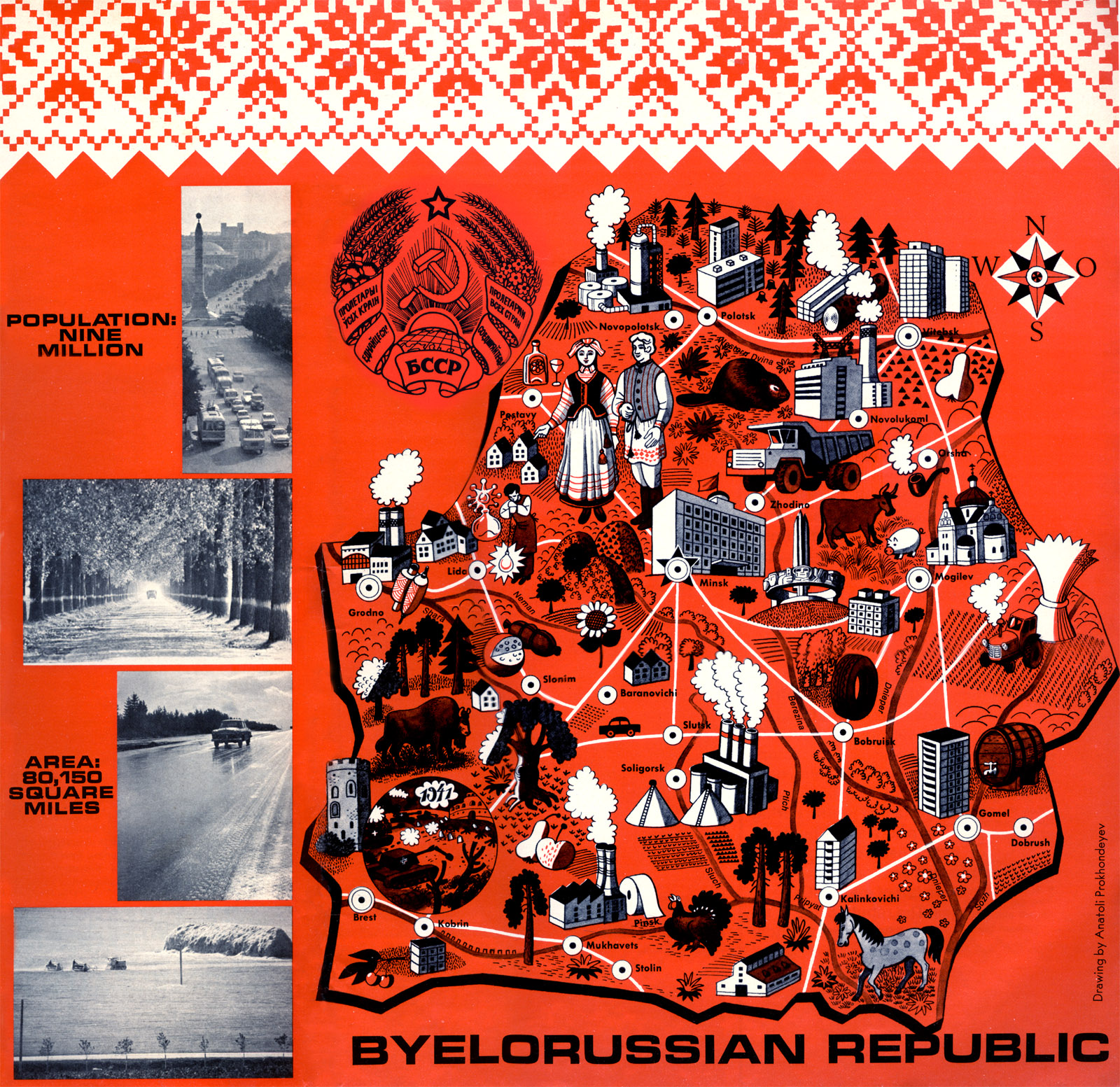

This map appeared in the front cover of the December 1971 issue of Soviet Life magazine. Soviet Life, as you might have guessed, has grown along with its namesake, becoming Russian Life today. Back in the 1970s, the magazine presented the Soviet Union in a less-than-propagandic way, avoiding too much political content and focusing on common life in the USSR. It made it into the hands of Americans, under the agreement that the Soviet regime would distribute the magazine America to citizens of Russia. In this issue, we learn of Belorussia’s contributions to the world, its participation in WWII and the United Nations, and its advances in arts and sciences. Most all of the article content can be found condensed into this illustrated map, showing off everything from classic styles of dress to cheese to construction equipment. The big logo in the middle is the Soviet-era symbol of Belarus, slightly different from an earlier style (which in turn was based on a general Soviet symbol): today’s symbol is strikingly similar, but exchanging the hammer and sickle for their own nation’s outline. While retaining some Soviet symbolism, the country changed its name from the Soviet-sounding “Belorussia” to “Belarus” with their independence.